The Theory of Constraints is the most powerful framework for action I’ve ever encountered.

Known as TOC, it offers a set of principles that can be used to make any system more effective. Any system, from manufacturing lines to oil pipelines to data centers to the human body.

And yet TOC, first developed starting in the 1970s, has been almost lost to the modern, digital-centric world. We’ve forgotten the lessons from decades of industry and manufacturing, and are therefore doomed to repeat the same mistakes.

My goal is to reintroduce TOC to a new generation, while showing that it applies just as much to our fast-paced, Internet-powered, digital-centric world as to the industries of the past.

Eliyahu Goldratt laid out the Theory of Constraints in his 1984 best-selling book The Goal. It was an unusual book for its time — a “business novel” — telling the story of a factory manager in the post-industrial Midwest struggling with his plant.

For 30 years now, readers have recognized their own situation in this fictional story. The Goal has become one of the best-selling non-fiction books of the past few decades, as people applied its lessons to fields as diverse as medicine, the military, software development, and the layout of buildings.

TOC begins with a simple principle: that every system has one bottleneck tighter than all the others, which we call the “constraint.”

For some systems you can see it plainly: the cars always slowing to a stop in that same section of freeway; that doorway in the office where everyone’s paths seem to converge; that one curve of your plumbing that you can’t seem to keep unclogged.

For other types of systems, it’s less obvious. It helps to broaden the concept from bottlenecks to constraints of any kind.

What is the constraint preventing a coffee shop from serving more customers? It could be the rate of cappuccino preparation, the speed of credit card approval, or the number of people wanting coffee in that place and time for that price. If it’s popular enough, the constraint could even be the width of the doors!

It’s not always easy to tell where the constraint is actually. But we know it’s lurking there somewhere, or else the coffee shop could serve an infinite number of customers at infinite speed.

What is the constraint keeping the human body – let’s take Usain Bolt’s for example – from running faster? It could be his body’s ability to metabolize glucose or oxygenate his muscles; or his shoe’s grip on the track surface; or a limiting belief somewhere in the depths of his mind that keeps him from giving his all.

Clearly, it gets even harder to find the constraint once we enter the world of the abstract, the psychological, and the immaterial. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

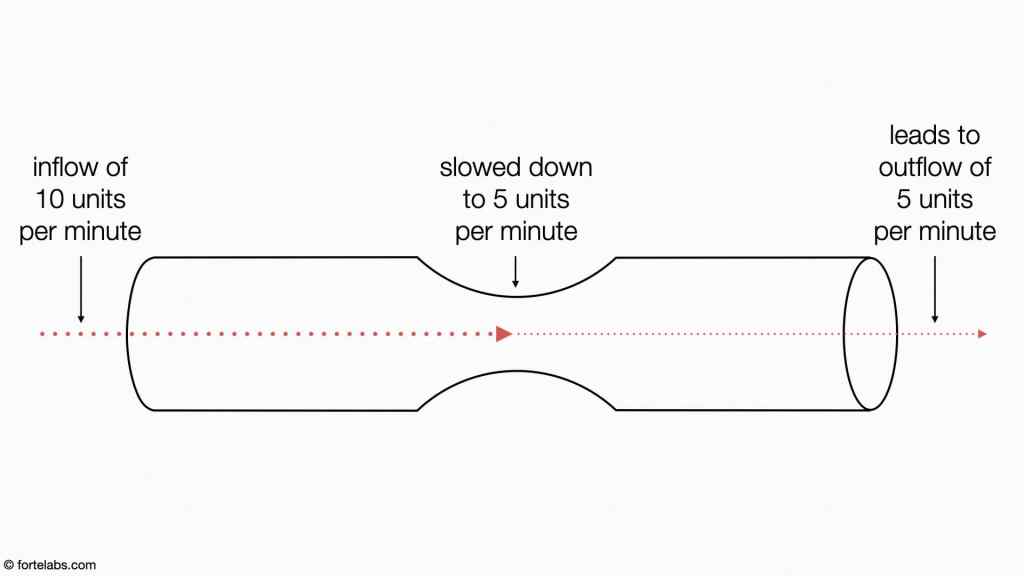

The second principle of TOC is that the performance of the system as a whole is limited by the output of its tightest bottleneck.

In other words, if the water in a pipe is slowed down to a trickle by a narrow section, the outflow at the end of the pipe can be no more than a trickle. This one is harder to see intuitively, because it is obscured by the messiness of the systems we typically interact with.

If a coffee shop’s bottleneck is the speed of its cash register, then it cannot serve customers one iota faster than the speed of its cash register. If Usain Bolt’s bottleneck is the proportion of his fast twitch muscle fibers, then he cannot shave one microsecond off his time without increasing them.

In other words, the overall capacity of any system is limited to the capacity of its tightest bottleneck, or more broadly, its most limiting constraint.

The third principle follows from the first two, but is the most profound and hardest to swallow.

It is the red pill of TOC: if the first and second principles hold, then the only way to improve the overall performance of a system is to improve the capacity of its bottleneck (or more broadly, the performance of its constraint).

Using the coffee shop example, if the most limiting constraint is the cash register, literally nothing else will make a difference to the bottom line except an improvement in cash register speed. Not better customer service, not higher quality food, not better interior decoration, not faster WiFi or cleaner bathrooms or stronger coffee or any one of a million other ideas.

Any improvement not at the constraint is an illusion, for the same reason there’s no way to strengthen a chain without strengthening its weakest link.

Now think about how a typical company operates.

The CEO announces “It’s time for the company to improve results! Everyone has to pull their weight!” That command gets translated down the ranks, each manager impressing upon his team the importance of their individual efforts.

Each person hears what they want to hear: the accountants understand that they must improve the usefulness of the books they keep (with each person interpreting “usefulness” differently). The software developers nod in agreement that better code is crucial (with each person interpreting “better” differently). The marketing people agree that more creative promotions are the only solution (with no one bothering to define “creativity”).

Each person interprets their CEO’s directive differently, according to whatever metric they find most natural, desirable, or easiest to understand. Each of them marches off on their personal mission, nose to the grindstone, without realizing that their collective efforts imply a management philosophy:

Local improvements everywhere automatically translate into the global improvement of the organization.

John Maynard Keynes once said, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

What if this implied management philosophy was dead wrong? What if, by believing that we can improve a system as a whole by individually improving each part, we are living and working according to an economic paradigm that has been defunct for decades?

That is exactly what the Theory of Constraints proposes, and the problem it seeks to resolve next.

Follow us for the latest updates and insights around productivity and Building a Second Brain on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. And if you're ready to start building your Second Brain, get the book and learn the proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential.

- POSTED IN: Flow